“The faded but not forgotten” history of Boblo Island

Director Aaron Schillinger talks about his first directorial debut film, Boblo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale, and its history

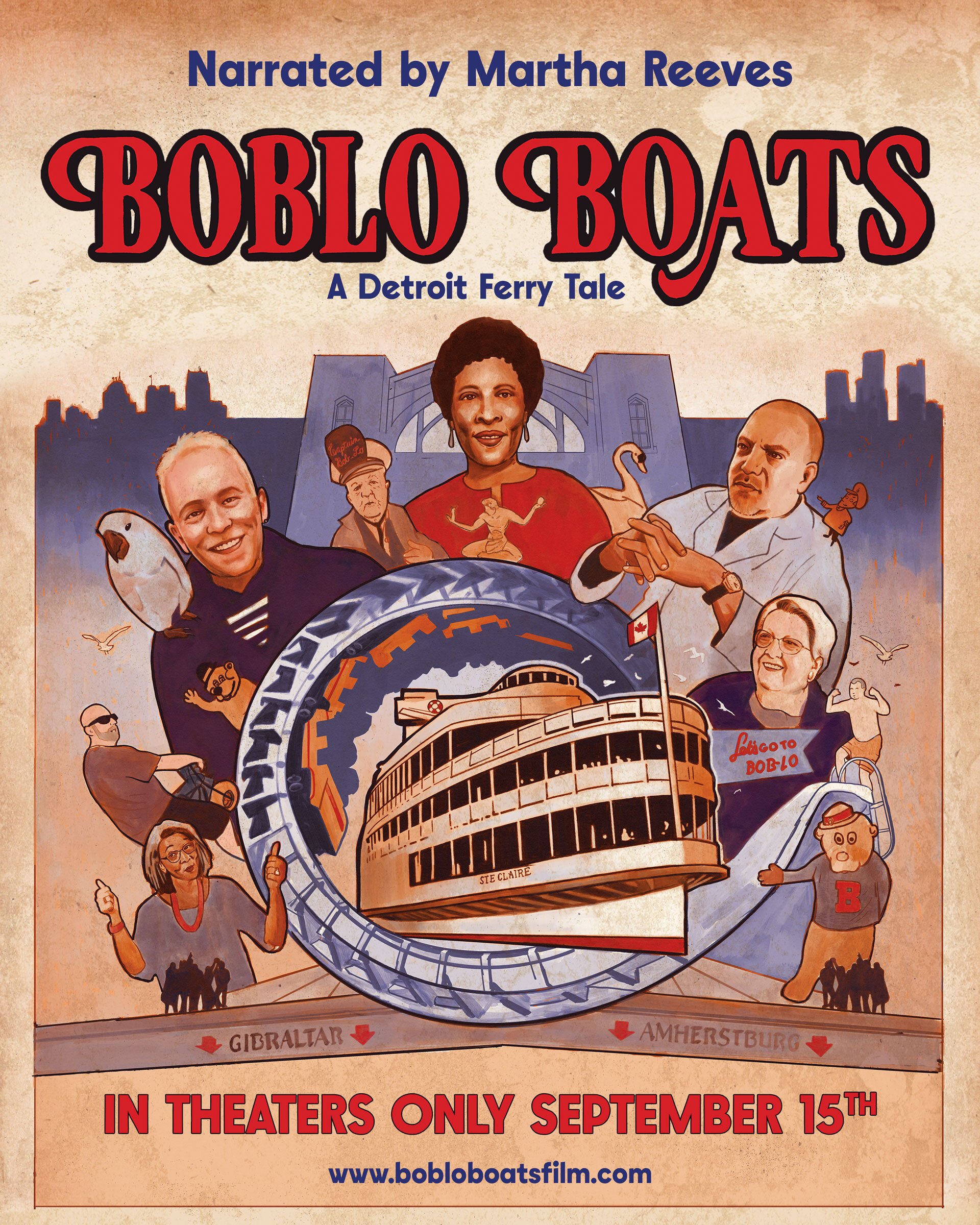

Flint, Michigan — “This river is my home,” begins the legendary Motown artist Martha Reeves as she narrates and sets the stage for Aaron Schillinger’s directorial debut film Boblo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale. “I can tell you the names of every current and eddy that flows along the shores of Boblo Island,” Reeves continues as the Columbia and the Ste. Claire flashes up on the screen and injects themselves into the hearts of us seated inside the theater.

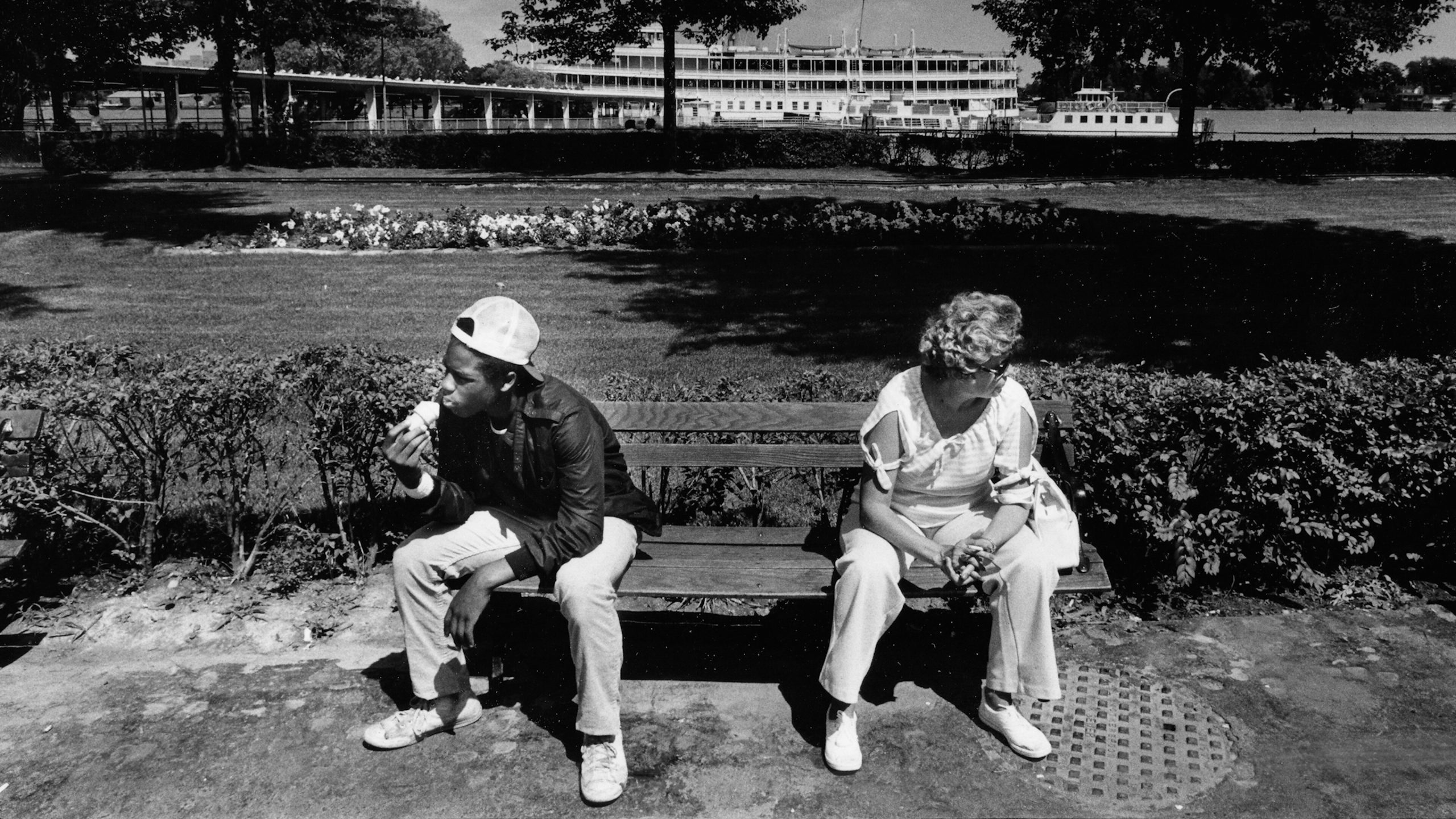

The story of Boblo Island begins in 1898 as an amusement park that initially allowed access to only white Americans. The park, located in Ontario, Canada, became the destination for Detroit natives, which included riding upon the oldest steamboats in America. But while nostalgia is present, there are things people had forgotten—like the untold history of the black-owned Sugar Island, an African American equivalent to Boblo Island, before it was mysteriously cut short.

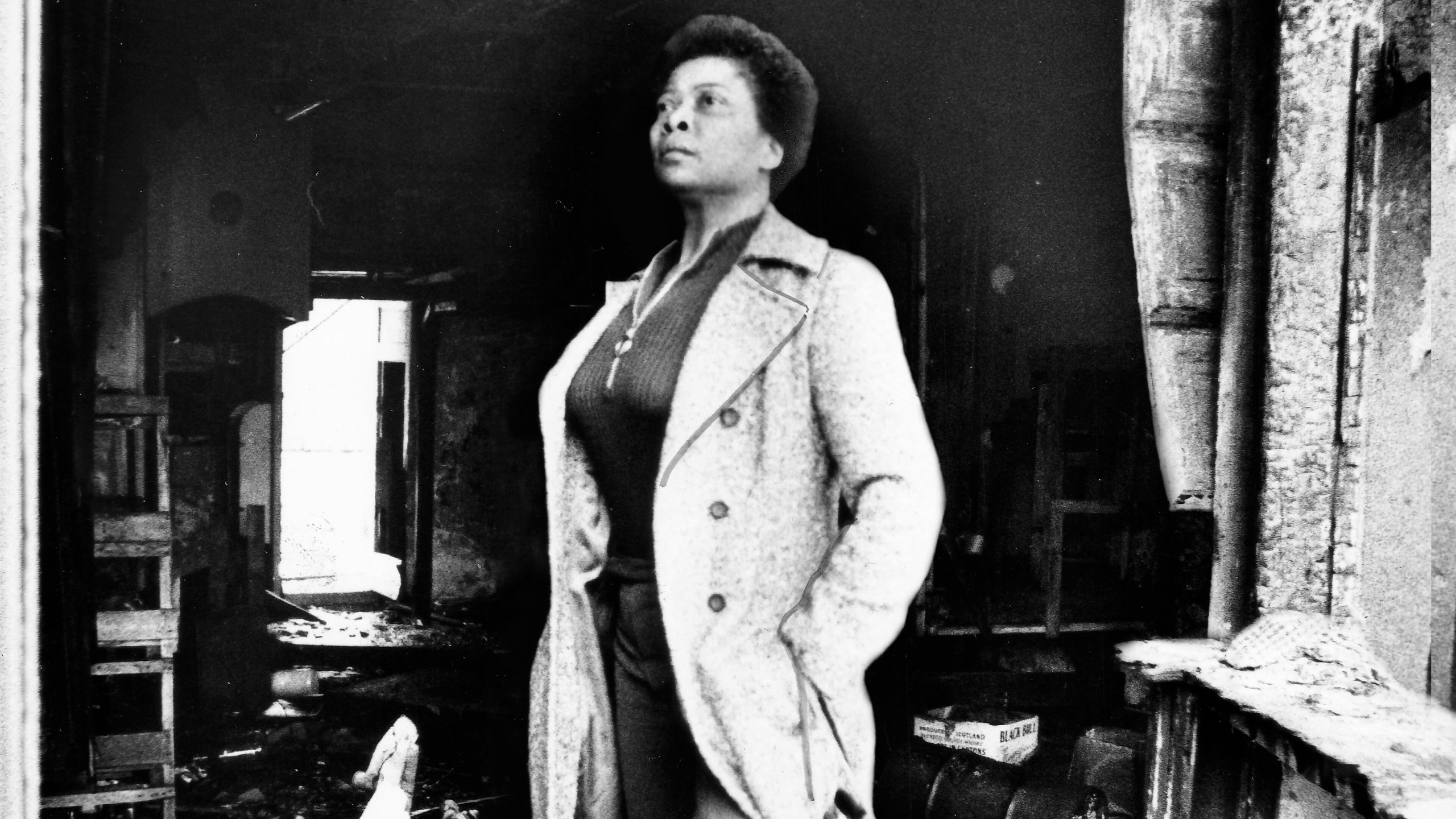

Or how in 1945, when Sarah Elizabeth Ray, a black woman, sued the Bob-Lo Excursion Company and won for denying her passage because of her race. Through the help of the NAACP and Thurgood Marshall, her victory desegregated Boblo Island and became the precursor to the landmark Brown v Board of Education. Moreover, her success opened the floodgates for Detroit’s black population to ride the boats and participate in the island’s legacy. But it wasn’t just there. It was everywhere, including Flint.

Flintside spoke with Aaron Schillinger, writer, director, and editor of Boblo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale, Flint native Eartha Logan, and Lansing resident Denise Weber about Boblo’s history, making the film, and its civil rights roots.

Flintside: Spirituality and metaphysics are some of the underlying themes in this documentary. Why is that?

A. Schillinger: “Boats, in general, [have] a lot of superstitions surrounding them. They’re referred to as females with the pronouns she and her. There’s not many objects that you refer to like a person. Even the ships themselves are sisters. [So] they’re treated differently than any other objects. There were some ghost stories, but I tried to include these other perspectives that were a little mythic. I feel to capture what it felt like to go on this epic journey as a kid [was] to bring that magic and mysticism into the movie.”

Flintside: Although what opened the floodgates for this film was Gloria the psychic and Dr. Ron Kattoo, the owner of the Ste. Claire, there’s a significant focus on the character Kevin and his relationship to Boblo Island and the boats. So what made him stand out?

A. Schillinger: “When telling a feature-length film, you want some emotional stakes. That’s what Kevin’s story is. His character arc essentially reconciles with his past because he has difficulty accepting that [Boblo Island] closed down. He spends all this time trying to save the boat almost as a way to preserve the past. I felt including Kevin’s story would give an emotional outlet for those people who also felt a longing for Boblo.”

Flintside: There’s a line in the film saying this movie isn’t a fairytale. Some tragic things happen, with the fire being a particularly striking moment. What was the significance of that?

A. Schillinger: “Kevin had a character arc where you see him go back to Boblo and deal with his past. But what about the boat? What about the people of Detroit? When I found out [what happened], I immediately went to the airport. I wanted to capture that in film. Nobody would expect that, but I think it’s a little beautiful. There’s a quote towards the end, and there’s people talking about Detroit being rebuilt. The slogan of Detroit is ‘rise from the ashes.’ [So] when the boat catches fire, it’s a cathartic moment even though it’s tragic.”

Flintside: What were some of the personal struggles that you endured?

A. Schillinger: “I spent a lot of my savings and [went] into debt that first summer. The most emotional moment for me was when I decided that I had enough footage to start editing. I would sit down, and I would have panic attacks. In my mind, I wanted this movie to be this epic fairytale and [facing] the reality of what we had. It was difficult for me, and it was some dark nights. One of the themes is reconciling this happy, fun nostalgia with the reality that these places were segregated.”

Flintside: How important was it to include this untold, unspoken history of Boblo Island and the sister boats?

A. Schillinger: “The Black Lives Matter Movement was a huge part of [my journey] because I had the Sarah Elizabeth Ray story. [However], when it came to Sarah Elizbeth Ray and Sugar Island, almost nobody knew about those histories. I had to rely on academics and historians to gimme that context. Desiree Cooper provides the background on [Sarah’s] story. Boblo was segregated, and black people weren’t allowed to go except on a Monday. That’s when I came upon the story of Sugar Island. [Detroit’s Chief Historian] Jamon Jordan says Sugar Island was an ingenious black solution of ‘let’s buy our own park.’ Had it not shut down, we could of had a white Boblo Island and black Sugar Island.”

Flintside: For you, Ms. Eartha, going to Boblo Island represented a different era. What were your experiences?

Ms. Eartha: “Boblo Island was a famous picnic area for our black churches. When we had Sunday school picnics, that’s where we started going. If you had your little boyfriend that you liked, y’all would try and get your little cubby hole where that’d be y’all chance to sit next to each other. [But] as we got older and got families, that’s where we would take them for the 4th of July. We would love to see the fireworks going off on the Detroit River.”

Flintside: I imagine for you too, Ms. Weber, that it was the same.

Ms. Weber: “It was always big groups of people having a good time. There were 10-20 of us, families, and friends from church. We would probably go four or five times a summer, from [when] I was about six to 18 years old. My favorite thing was the ride home, the slow cruise with the dancing and the music, and the night sky off the boat.”

Flintside: Aaron, now that the film’s finished, what have you learned from all this?

A. Schillinger: “I’ve learned that you have to be careful what journey you start on because you don’t know how long it’s gonna be and where it will lead you. I moved to Detroit in 2020 because I wanted to finish the film here. Then I met this woman, we got married in April, and now I’m here to stay. Michigan is now my home, and it’s all because of an amusement park that closed down in 1993. It’s taught me to pay attention to anybody who’s got a story. You never know when that might [take] you on this surreal life-changing course.”

To learn more about the Boblo Boat’s film and story, visit their website or check out their Facebook and Instagram. Additionally, you can find the story and ongoing restoration of Sarah E. Ray’s history at https://www.detroitsotherrosaparks.com/. Boblo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale is playing in select theatres across Michigan, including Emagine Birch Run, beginning Sept. 30. Tickets are on sale now.