Flint’s community model for schools swept the nation but is now a forgotten relic

Flintside photo-journalist Jenifer Veloso takes a deep dive into the origin of Flint's community model for schools and gives an inside look at the ruins of schools left behind in the city.

FLINT, Michigan — In the 1930s, public schools underwent a massive transformation after the debut and success of the “lighted schoolhouses” that started in Flint, Michigan. Neighborhood public schools across America became centers for community enrichment and development. This entire idea and model to make schools community centers for residents was started through the partnership of Charles Stewart Mott of the Mott Foundation and Frank J. Manley, the executive director of the Mott Foundation’s projects.

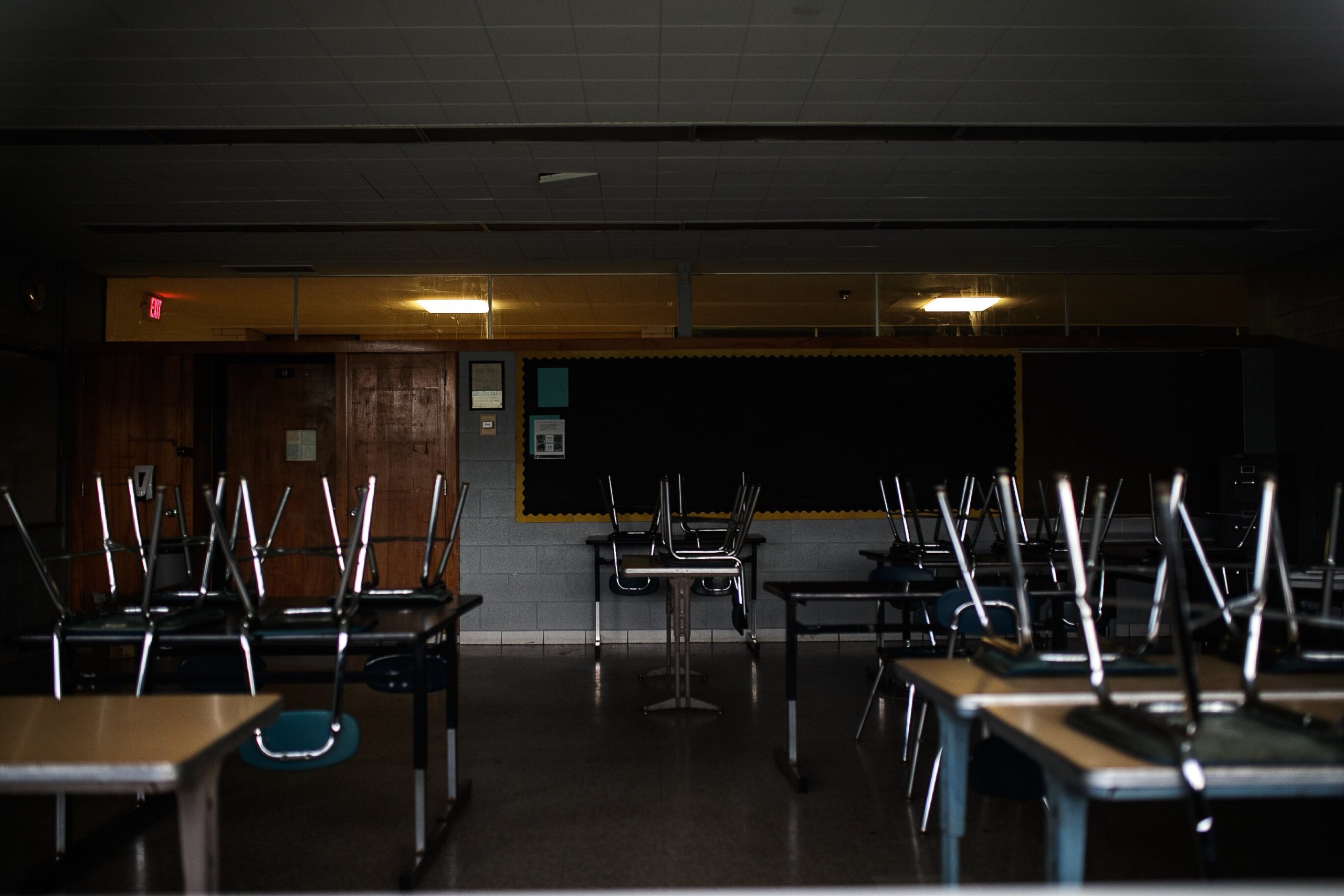

The community model for schools is hard to imagine in Flint considering the current socio-economic condition and the current state of Flint schools. Today, more than 20 Flint schools have closed as the city continues to have a decreasing population, a revolving door of superintendents, and a multi-million dollar deficit. The city now is riddled with empty and abandoned school buildings as a reminder of the past and a looming question of what the future of Flint schools may hold.

After the Great Depression, Flint’s education system was in critical condition. In Andrew Highsmith’s book Demolition Means Progress, he described the then economic and public environment: “…decreasing tax rolls and declining population forced the Flint Board of Education to curtail both the length of school days and the duration of the school year. With neither a traditional school calendar nor an adequate system of recreation, thousands of unsupervised children often gathered for play on the streets, in the Flint River, and in other dangerous places. Consequently, juvenile delinquency and a ‘steady mounting traffic slaughter’ of child pedestrians became grave social problems in Flint’s crowded central city neighborhoods.”

Manley studied physical education at Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti and believed in the importance of school-based programs. He arrived in Flint in 1927, and a year later, began to oversee the physical education programs in the city and quickly recognized the alarming situation children in the city of Flint were in. Manley is reported to have said in Highsmith’s book, “Every year we have eight or nine children killed while playing in the streets. Scores of others are becoming juvenile delinquents because we don‘t like the way they utilize their leisure. Who‘s to blame? We are, because we don‘t give them any place to play but the streets, and we don‘t provide any recreation or amusement for them.”

Manley’s understanding and perspective of the disservice being done to children differ very little from the current reality Flint children face now. U.S News reported on data collected during 2017-2019 in Flint that the city contains 14 schools and 3,748 students with the district’s minority enrollment at 90% and 80.5% of students are economically disadvantaged.

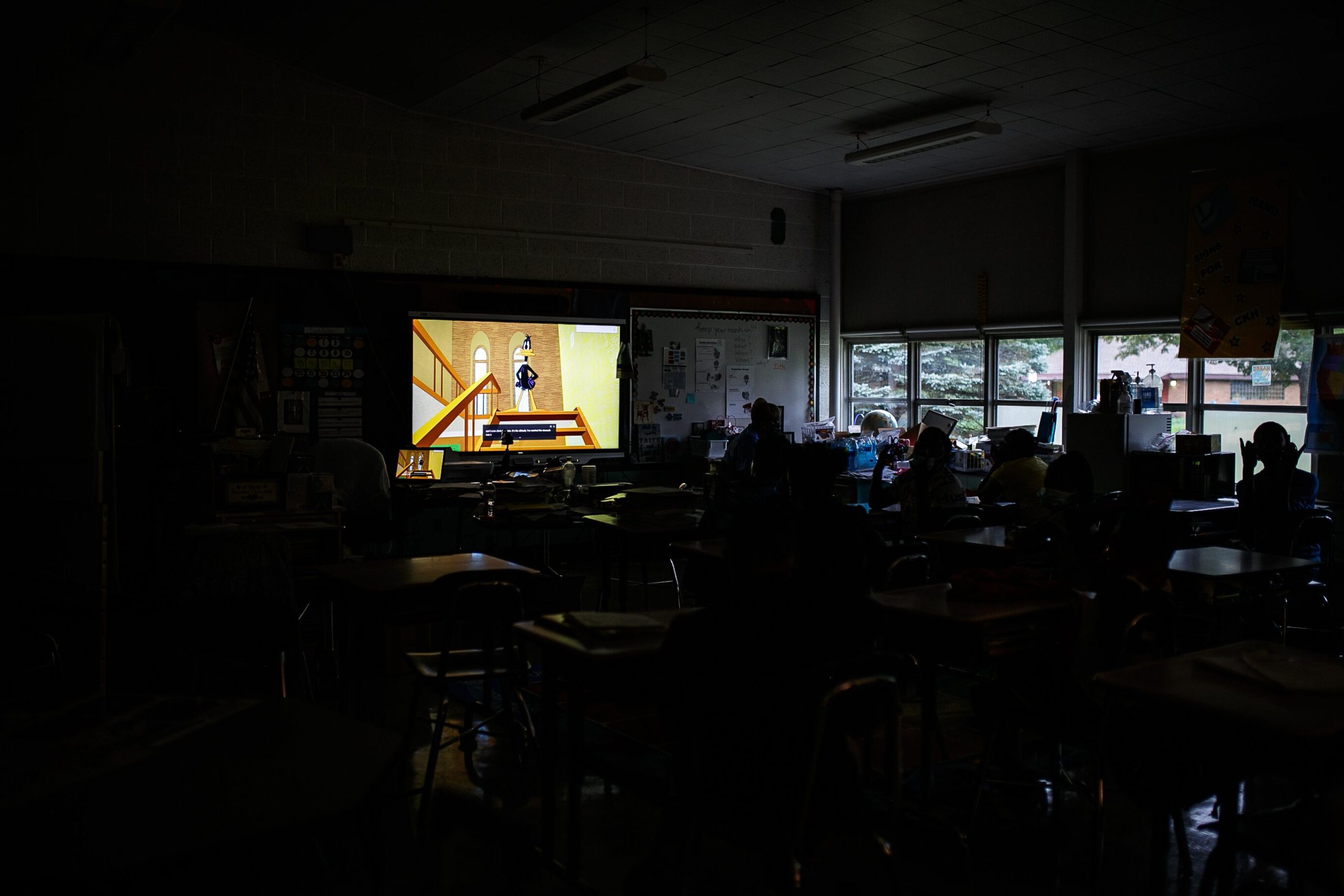

During the beginning of the 2021 school year, Doyle-Ryder Elementary students were displaced to other Flint schools due to mold identified in classrooms. In August of this year, Flint Community Schools were forced to cancel classes due to high temperatures and the schools not having central air for relief. The classroom temperatures were reported to be unbearable and citing temperatures in the mid-to-high 80s.

Many of the historic schools in Flint due to the rapid decline in population have remained abandoned. Washington Elementary, a one-hundred-year-old school, closed its doors in 2013. Over the last eight years, the school has been vandalized, burned, and become increasingly structurally unsafe. On October 7th of this year, the school was finally destroyed by arson.

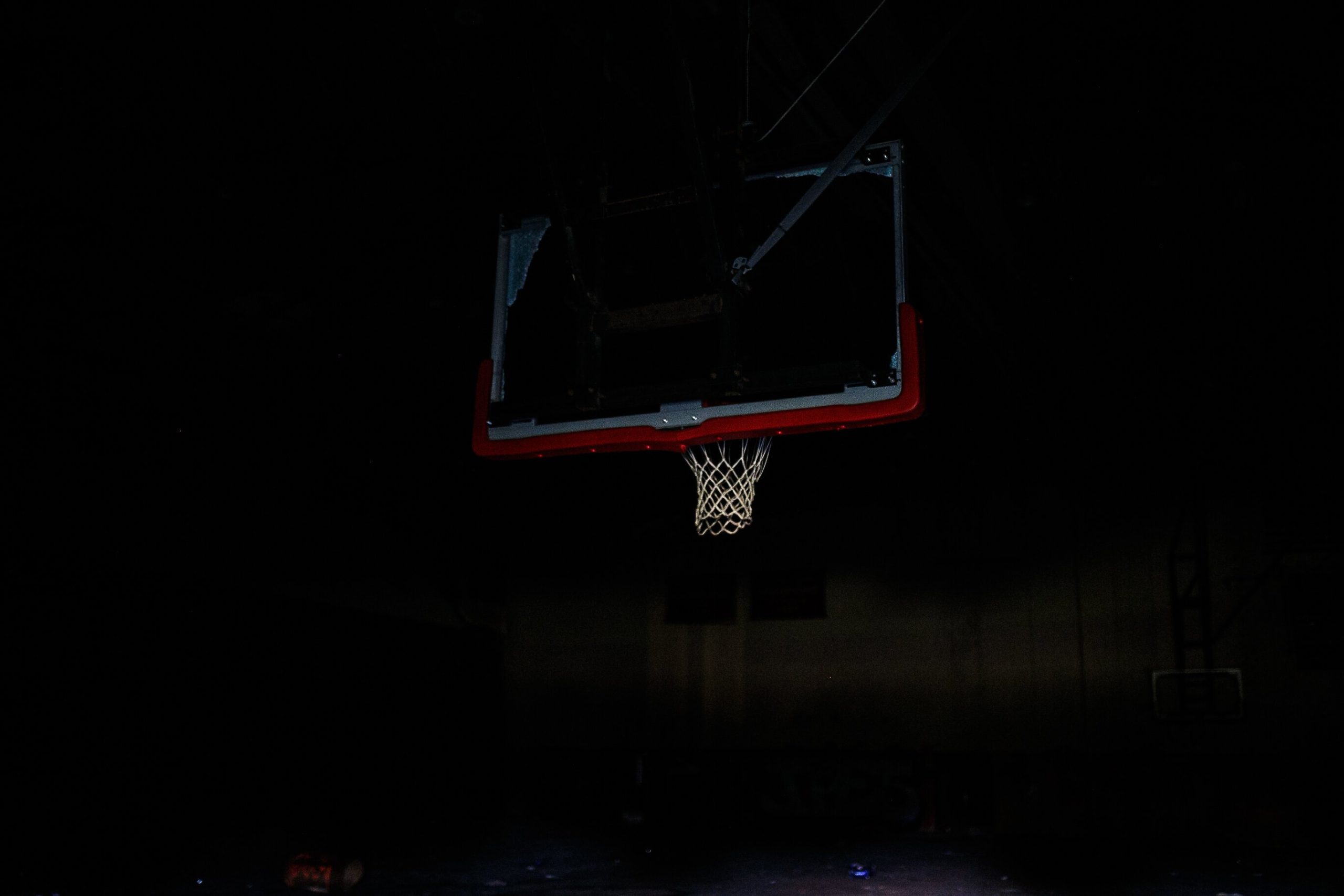

The dream Manley and Mott envisioned for communities were to ensure that residents in the different neighborhoods of Flint had a place to engage, learn, and grow together. In 1972, an article written on Flint schools stated, “…schools all over the world pattern their recreation programs after the Flint model. The schools of Flint surely have the most elaborate physical education facilities in the U.S., at least for municipalities of its size. Flint gymnasiums are not just courts for playing basketball. They are enlarged facilities that can accommodate various kinds of activities simultaneously.”

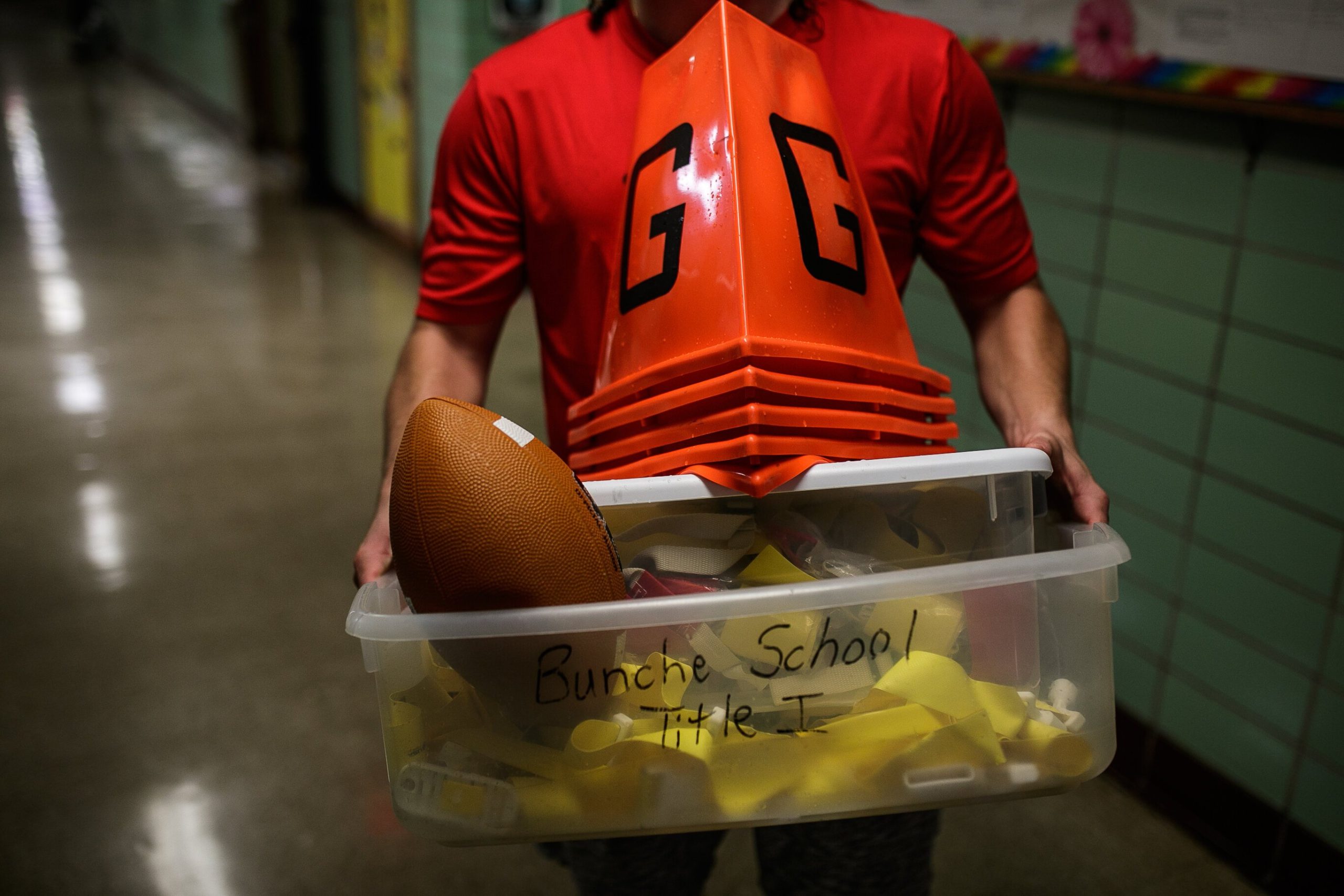

Local organizations and residents are still fighting to find ways to provide extracurricular activities for the current student population in Flint. The Crim Foundation is offering a 2019-2020 sports program for free to all Flint community school students. The programs are held and led at local school sites.

In a press release earlier this summer from Ridgway White, Mott Foundation president and CEO, stated that “The Mott Foundation will grant a total of $7 million to Genesee Area Focus Fund and Crim to ensure that YouthQuest and the Community Education Initiative can continue serving Flint kids and families through the 2021-22 school year. We also remain committed to working with Flint Community Schools and the Board of Education, and we would welcome the chance to resume a dialogue around creating a future that is bright for all Flint kids.”

Another plan the Flint School Board has to help the communities that surround the abandoned schools is to offer some of the abandoned buildings to be bid on by potential buyers. The bidding process is being organized by Thrun Law Firm, Flint school’s contractor. Attorney Gordon VanWieren from Thrun Law Firm was quoted recently stating, “This is not a situation where the board of education would have to sell the property to the highest bidder, but rather the board would ask what is in the best interest of the school district through the community.”

Mott and Manley’s vision for Flint schools was one that could be replicated and reused nationwide. By the end of 1970, The Flint Journal reported that the Mott Foundation’s publicity campaign for the community education programs spread to over three hundred school districts nationwide.

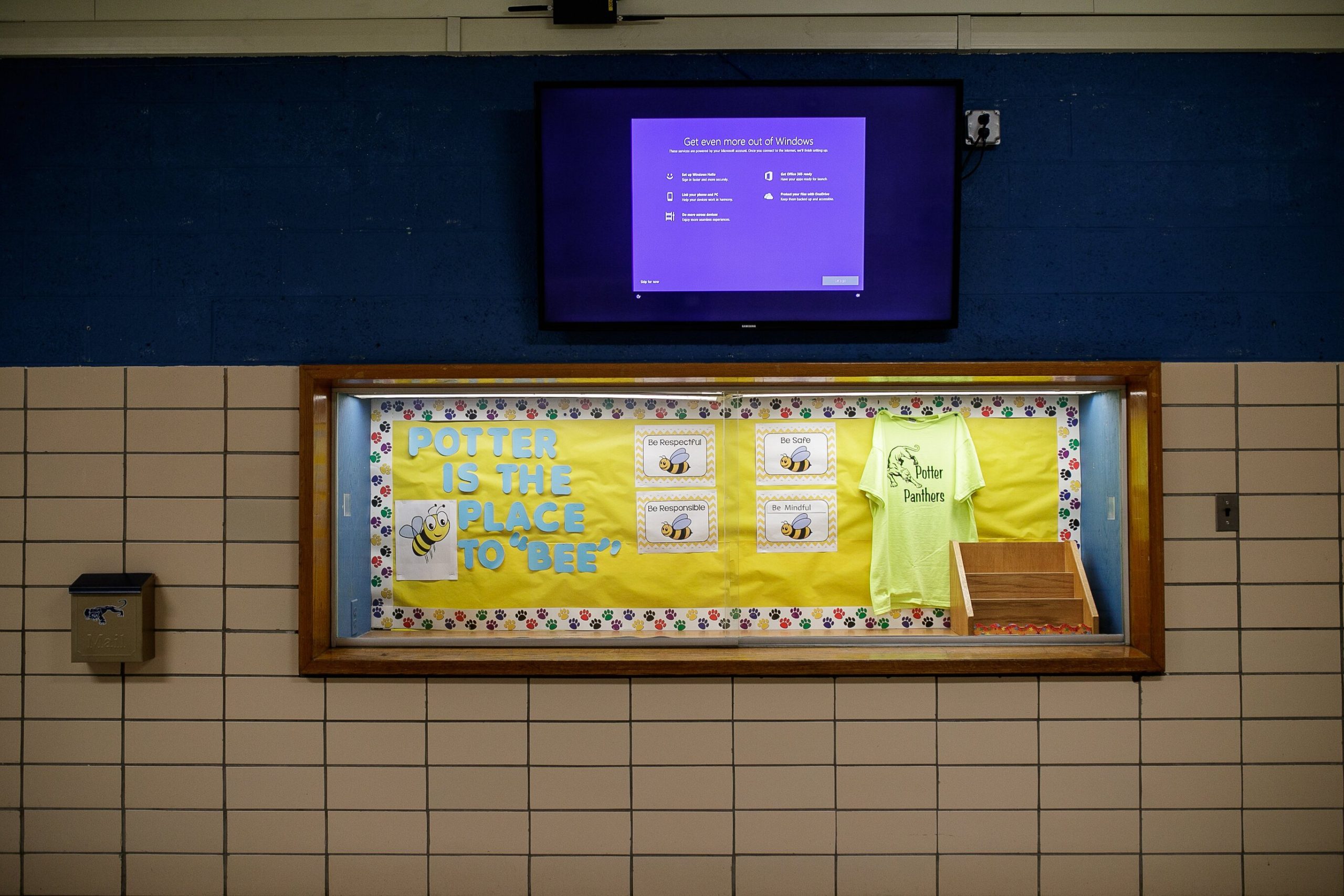

Potter elementary school was one of the elementary schools that took displaced children from Doyle-Ryder due to mold found in classrooms.

The future of Flint schools is not clear, but what is certain is that history repeats itself. The century-long segregation of neighborhoods, education, and neglect of the marginalized continue to show the reality of neglect in the community. Flint’s fight for a better education system is the fight that will truly determine the future of its residents.