As educators in Flint return to their classrooms, one teacher is making sure her seats are filled

One Flint teacher got creative to make her empty classroom come alive during online classes.

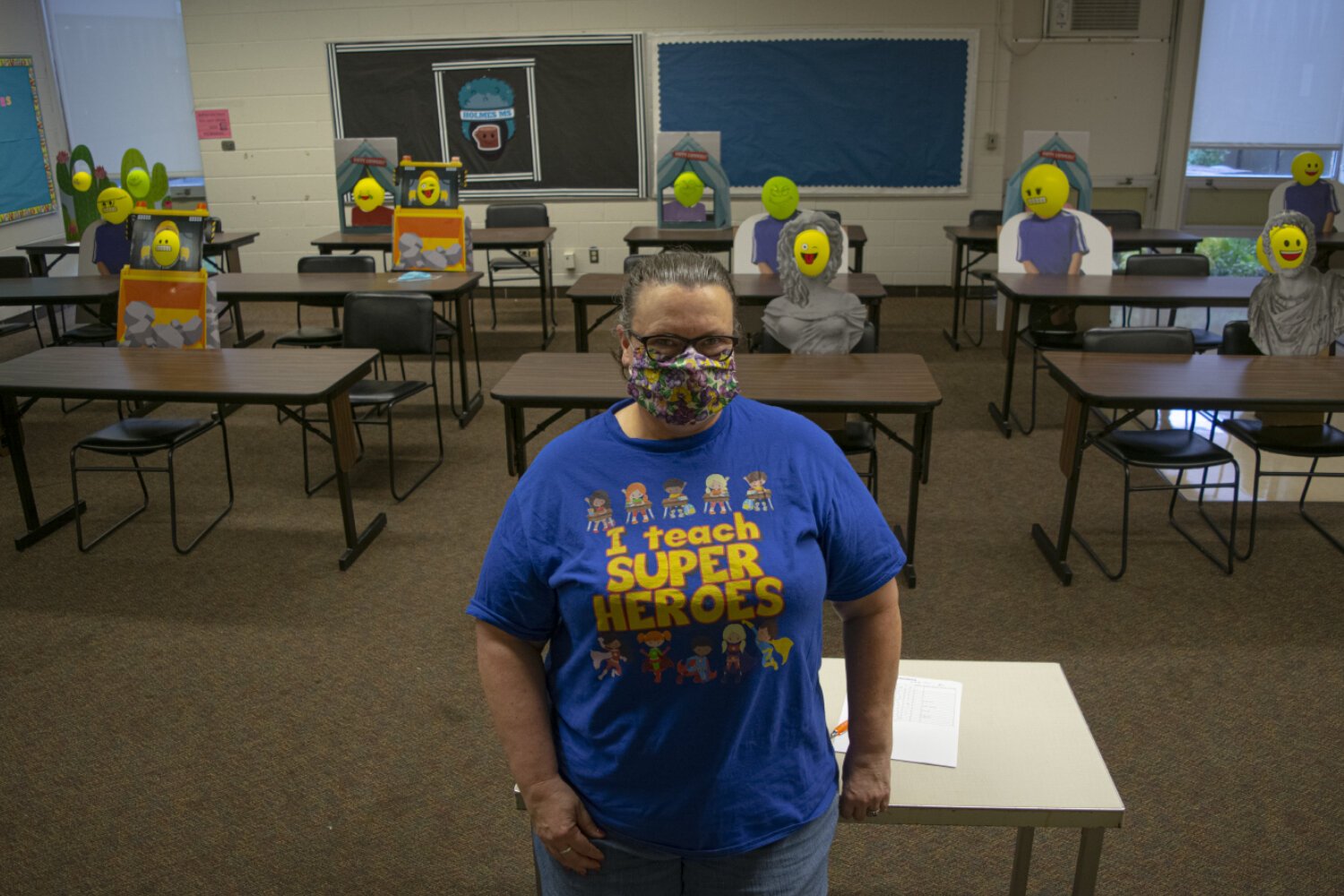

FLINT, Michigan — An empty classroom isn’t a classroom at all. At least that’s what Debra Olayinka, one of the many Flint educators getting ready to return to their classrooms says. Though her students will still be sitting in front of a screen miles away, Olayinka has found a way to fill her classroom’s empty seats.

Olayinka has been teaching for nearly 30 years, 17 of those in Flint. Currently, she’s teaching seventh and eighth graders health at Holmes STEM Middle School Academy.

If you were to ask any educator working during the pandemic what keeps them going, many would likely say their love for teaching and for their students. While at first glance Olayinka’s response may not be that different, if you speak with her long enough, you’ll see that same love is as much her biggest motivation as it is the hardest aspect of working virtually.

“The worst thing is not having kids here, it’s so painful for me. I’m used to hugging … I want to pinch their cheeks. To make contact, it’s so hard to do it through a screen, it’s so sterile,” says Olayinka, adding that part of being a teacher is being able to make sure students are doing okay. She wants to be able to look them in their eyes and see the emotions behind them. “They’re so far away and I can’t get to them.”

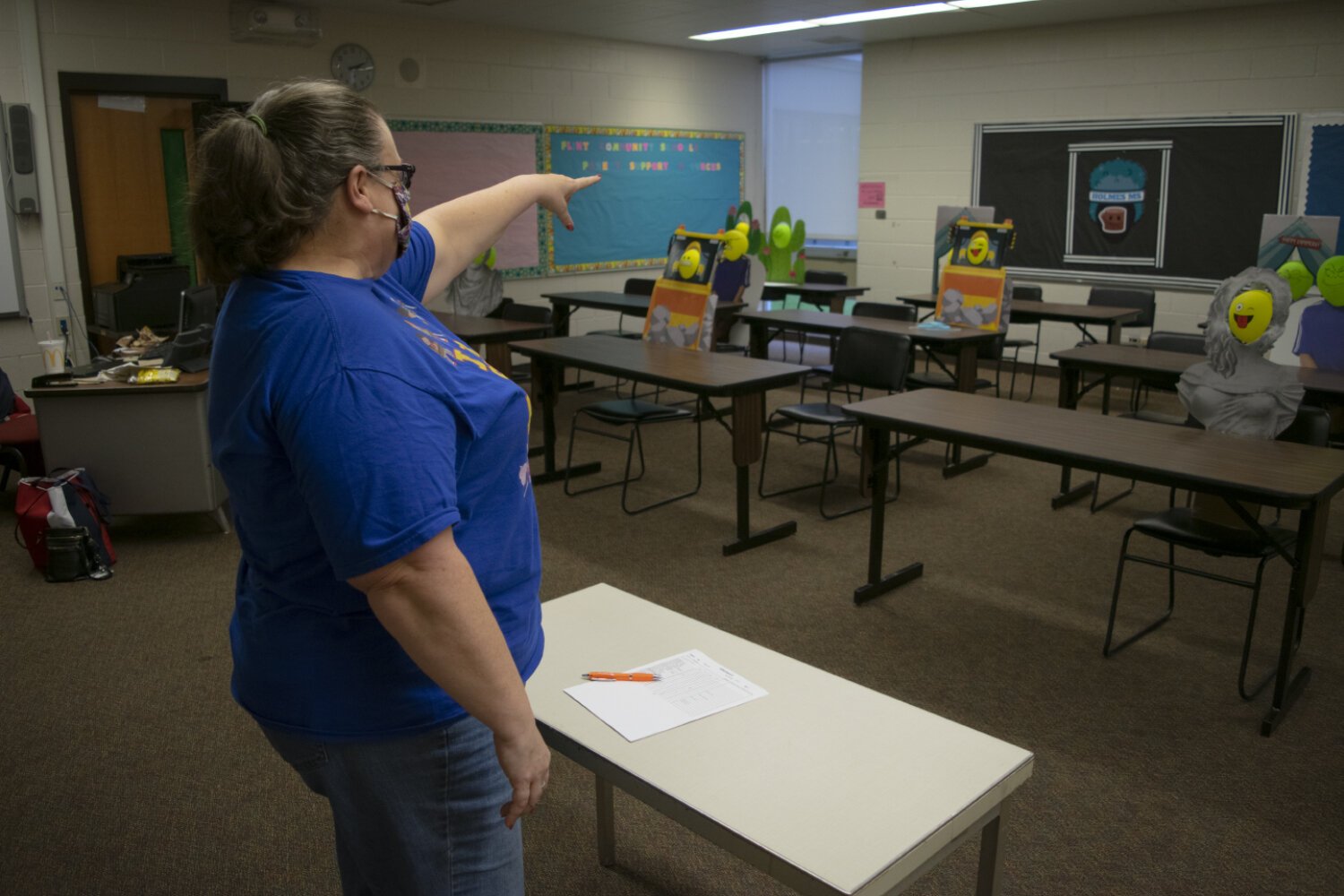

When she learned she’d be returning to the classroom, Olayinka was elated to be leaving the confines of her home. Despite this, she knew going back to an empty classroom would eventually be just as bad. A change of scenery is nice, but it can’t replace the comfort of dozens of eyes staring at you.

To remedy this, Olayinka took a page straight out of the National Football League’s COVID-19 playbook and filled her classroom’s seats with what can best be described as cardboard cutouts of students. “I was watching football and saw cardboard people sitting in the stands and I said ‘oh wow, that would be great,’” Olayinka said. “Then I could set up my camera and teach on the board to my students and to my pretend class. I thought I would feel much better and I do.”

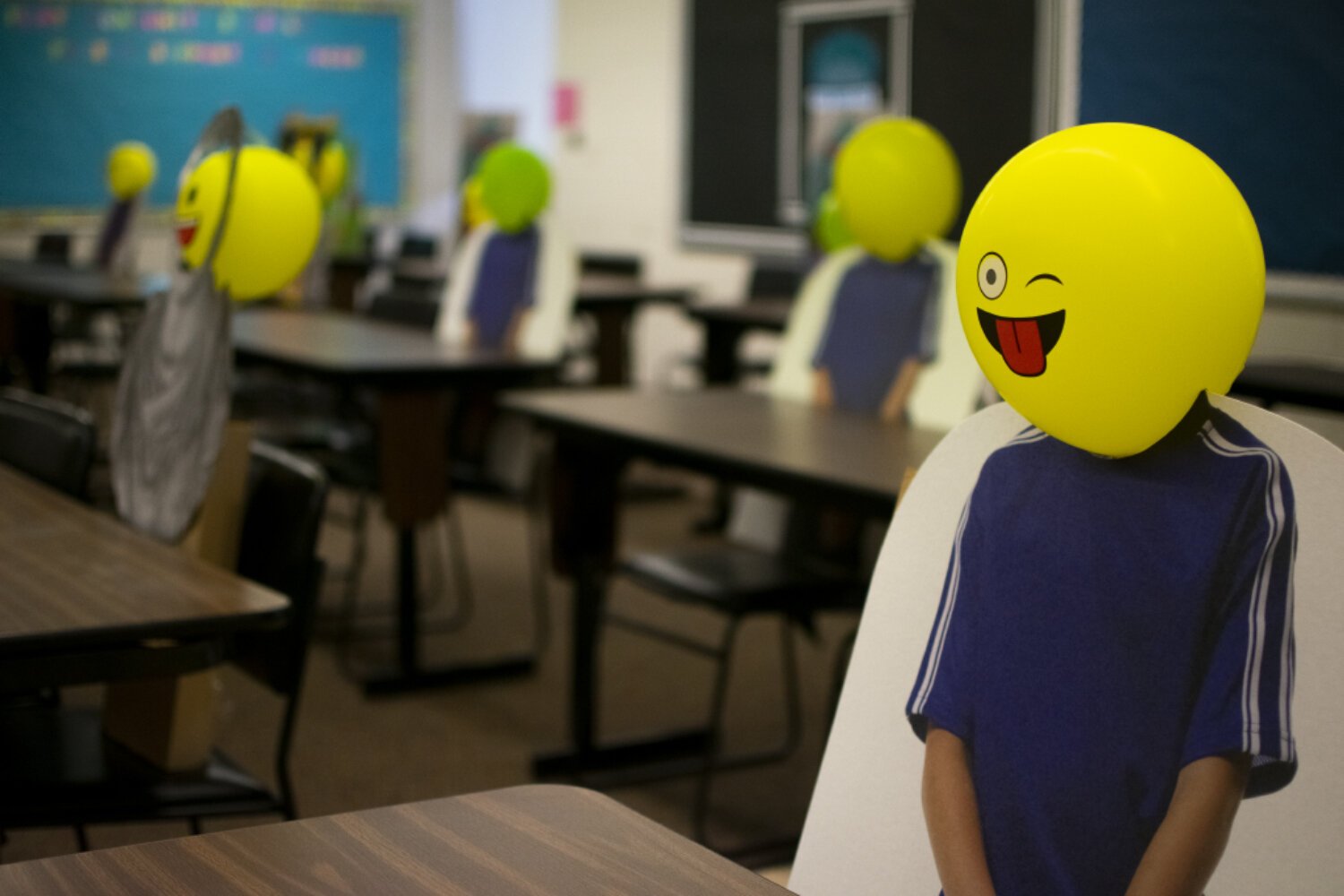

The term “students” is generous when referring to Olayinka’s cutouts. While a handful of them are of a blue-shirted child with an emoji-faced balloon for a head, about three-quarters of her students are either busts of important Roman figures like Julius Caesar, cactuses, heavy machine operators or carnival workers … all of them also with emoji-faced balloon heads.

It goes without saying that Olayinka has gone as far as to assign personality traits to her new students. The two cactus-students sitting together in clear violation of social-distancing guidelines for example are the trouble makers. A prickly pair if you will.

According to Olayinka, who introduced her students to their cardboard counterparts, the reactions were mixed. “Some students think it’s fabulous, other students were like ‘oh okay, but it looks a little weird to me.’”

Despite a lack of unanimous approval from her students, Olayinka says just having the cutouts present makes all the difference in the world for her. “I’m loving it … It’s amazing just having cardboard and balloons change my mood completely … You have to have coping mechanisms, you have to have outlets to release stress … my face hurts from grinning, I keep thinking of ways to improve it,” Olayinka said.

On top of teaching to her cutouts, Olayinka says she’s considering handing out fake assignments during class as well as pencils and notebooks. “I’m over the moon about the way this has changed my mood in the room.”

In the end, Olayinka says the cutouts are about being able to be her best self for her students. She does not hesitate to say online learning is hard for her and that teaching online at times can seem just as daunting. “I need to be with people, I need to see people, I need to be in groups … this isolation has been very difficult for me.”

According to Olayinka, the cutouts allow her to focus in on what she’s doing. Just like with her students, she finds it hard to stare at the screen for hours on end. Now at least, she can glance up from time to time and see emoji faces smiling, winking, and sticking their tongues at her. Just like a regular day at school.