Stitching together new lives (and Stormy Kromer gear) in north Flint

St. Luke NEW Life Center, which for 15 years has provided job training and hope, now makes vests and gloves for the iconic outdoor wear company.

FLINT, Michigan—On a snowy day in January of 2002, Sister Carol and Sister Judy stood on a corner along North Saginaw Street in Flint. They brought articles of clothing and some household items with them, and lunch. They had positioned themselves where they knew they would find the homeless. Sometimes that was near abandoned houses where the homeless lived. On this day, a lady they didn’t know walked up and asked if they had clothing for a newborn baby. “It’s not for me,” she said and told the story of a woman who had given birth alone the night before in an abandoned house next door and had wrapped the baby in her hoodie while going door to door to find anyone who could help. The woman invited the new mother and child into her house and called 911 and the two were taken to the hospital, but then could not be released until the baby had clothing and a car seat. The caring neighbor took it upon herself to find what they needed, even begging strangers to help the new mother. Then, she found the nuns waiting for whatever need came along. Sister Carol and the woman knelt in a snowbank that day sorting through the clothes until they found everything they needed.

Clothes and supplies for the neighbor to give the new mother and baby. And, a calling for Sister Carol Weber and Sister Judy Blake, who left that chance encounter saying, almost simultaneously to each other: “We’ve got to do more for the women in Flint.”

It was for the two nuns, both former educators, the beginning of St. Luke’s N.E.W (North End Women) Life Center—a place that has fed, educated, employed, and nurtured lives in the city for 15 years.

The two shared the story of their chance encounter on North Saginaw Street with church members at a town hall-type meeting and said, perhaps challenged, “What do you want to do?” The immediate response from the congregation was: We need to do something and we need you do it—which was, Sister Carol says, “perfect because it gave us the opportunity as educators the chance to do what needed to be done here.”

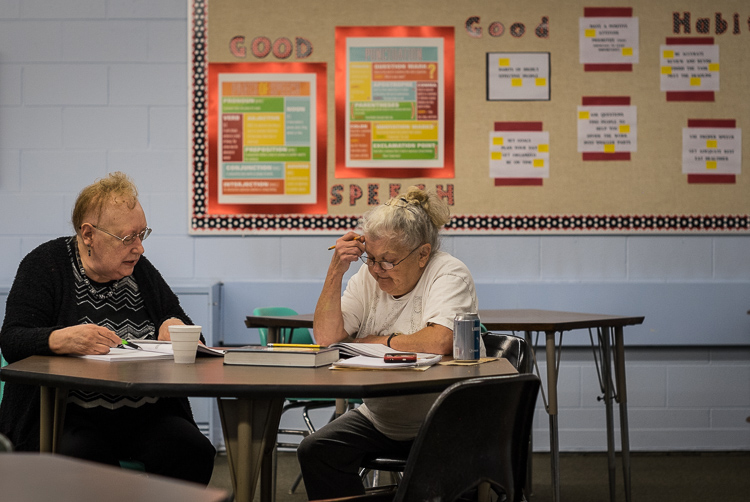

They got help from 42 women, all associated with a food pantry, to develop the goals for and the concept for a new center that would serve the women of Flint. It would be a safe place. It would be a place where women grow their self-esteem. It would be a place that provides an education.

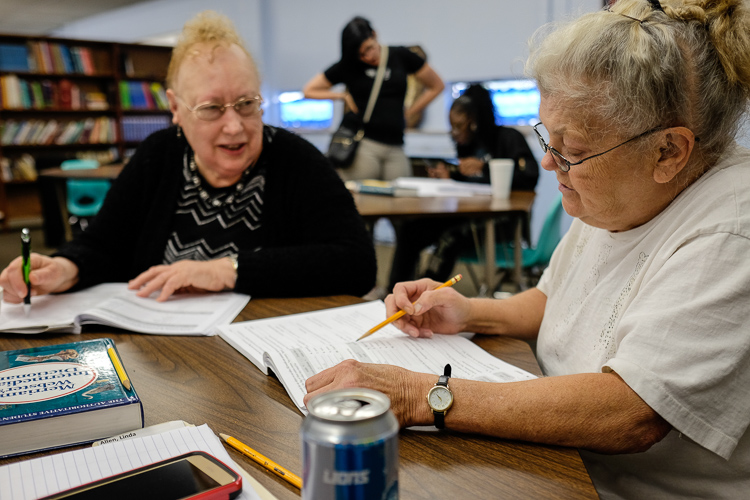

Shortly after the birth of the St. Luke N.E.W. Life Center, a literacy program was opened and programs were created to assist at-risk families so they could become self-sustainable. But the center found they couldn’t train patrons for jobs that didn’t exist. “So we decided to start a business,” Sister Carol says.

They chose to develop a sewing business. Given the number of medical facilities in and around Flint, they decided they could produce scrubs—the two-piece uniform worn in the medical field. St. Luke’s hired five women and sold the scrubs locally. It grew from there. St. Luke’s made 1,500 teddy bears for first responders to give to children involved in traumatic incidents and were asked to produce another 500 bears. Now, they produce vests and gloves for Stormy Kromer, the iconic national leader in outdoor wear based in Ironwood, Mich.

The vests are individually handcrafted on industrial sewing machines. Only a select few of the seamstresses at St. Luke’s perform the precision work. One of them is Nicole Zepp, a full-time employee, who says she has personally utilized almost every program offered at St. Luke’s including New Paths, food pantry, employment prep, and the literacy program. Another is Marty Calhoun of Flint Township, who also teaches sewing at St. Luke’s. The sewing that happens here at St. Luke’s is not just a job, Calhoun says: “It’s a personal ministry. There’s a lot of hope in this place.”

“It’s pretty high-powered and intense work,” says Sister Carol of the company’s exacting standards. The Stormy Kromer contract with the national retailer was and is a major boost to the reputation and opportunity for St. Luke’s. It even helped them land a contract with General Motors to create 4,000 air filters—with more orders already on the way.

“It helps people know that we know what we are doing. Not everyone can sew for Stormy Kromer,” Sister Carol says.

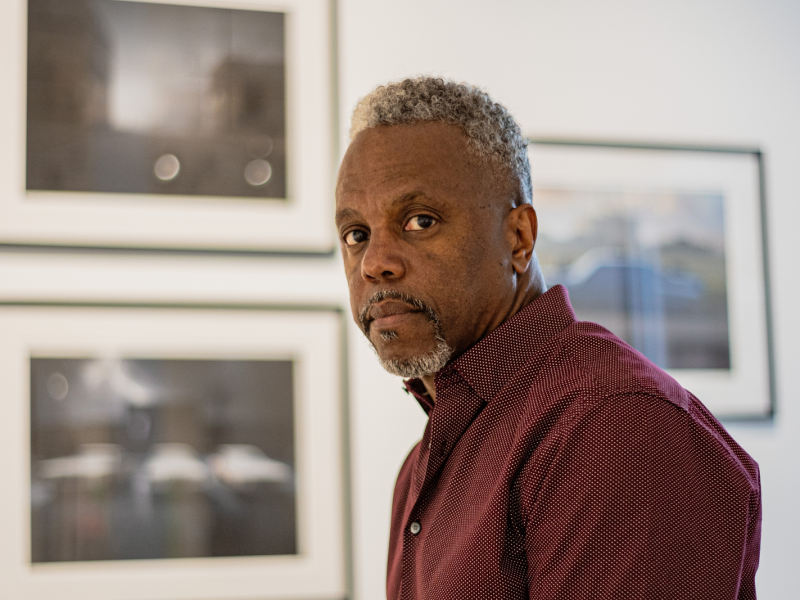

Although NEW Life Center initially was created to help women, men in the neighborhood soon approached the sisters looking for work. Sister Judy’s response: “Alright, give me some ideas.” We can cut grass, the men said. And, so, St. Luke’s launched a lawn care business, which now holds a contract to cut grass at properties owned by the Genesee County Land Bank and for the first time (barely) made a profit this year.

Men and women in St. Luke’s work programs complete 16 weeks of training—including computer training, working toward a GED, sewing, resume writing, problem solving, even exercise—as well as how to keep your job. Program participants then work for St. Luke’s for 90 days before the center starts trying to place them in a private sector job.

St. Luke’s looks specifically to help the “structurally unemployable”—a state term that includes those who have committed felonies, those who haven’t worked in at least a year, those with disabilities and those young people who fall into high risk categories. More simply put: “those that have no other option but to steal what they want or need,” Sister Judy says. “We are trying to make the neighborhood strong with men and women who know what they want and are willing to work for it.”

Sister Carol says: “We want to give them a chance at life. … The first step is listening to them, to their hurts and stories, and asking them what they are willing to do to change their life.”

St. Luke’s has an 80 percent success rate for employment in the private sector for those that complete the 16-week training program and the 90-day employment experience at the center. “That’s high,” says Sister Judy. The employment experience focuses on exploring different work opportunities and getting experience.

“They go away from here with a lot better self esteem than they came here with,” says Sister Carol. “They have some knowledge and some skills, but they also go away knowing that we are here for them.”

The sisters are working on pilot program with state legislators to allow for those who get jobs to stay on assistance for several months and three to six months and then gradually weaned off—instead of “pulling the rug out from under the feet of employees who are working at minimum wage.”

“There is no incentive to work. They do better on welfare,” the sisters say. “We are in the poorest of the poor in this quadrant, 48504 and 48505. We are trying to change that one person at a time. We believe the saying that ‘a job is going to stop a bullet.’ (With a job) you’re not going to have the time, you’re not going to have the energy at night nor would you have the need. You could be at home raising your family.”

And, that is really what it is all about. It is about that one mother and her child. It is about a community of women and men, mothers and fathers. It is about the lives they build today and the futures they build for their families.

“We’re trying to break a cycle of poverty and that’s probably one of the hardest things to do,” Sister Carol says. “We have people who come to us that have never known anyone in their home to go out to work.” The two nuns tell the story of Napoleon, who received training from St. Luke’s and then a job. His 3-year-old son asked: “Daddy where do you go everyday?”

“I go to work,” says the father. His son asked him what that is. With that, the father sat down with the boy and defined work—an activity necessary to pay rent, keep the lights on, to buy food and clothes. His son replied that he, too, wants a job and wants to work.

“Now that is a game changer for that whole family,” says Sister Carol. “We’re trying to break the cycle. If we can help the present generation to say yes to breaking the cycle, it’s their kids that are actually going to change it.”